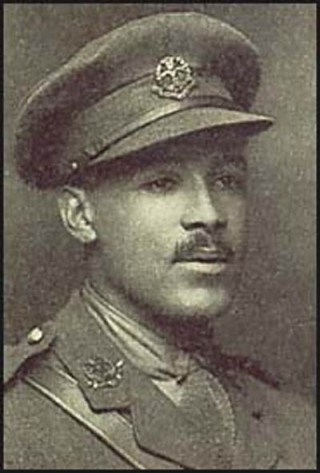

Walter Tull

Footballer soldier

Walter Daniel John Tull was born on 28 April, 1888, in Folkestone, Kent. His father, Daniel Tull, was a carpenter from Barbados and worked as a ships joiner when he arrived and settled in England. Walter’s mother, Alice Palmer, came from a family of farm labourers in West Hougham, Dover, Kent. Both Daniel and Alice were Methodists and met through the Methodist Church.

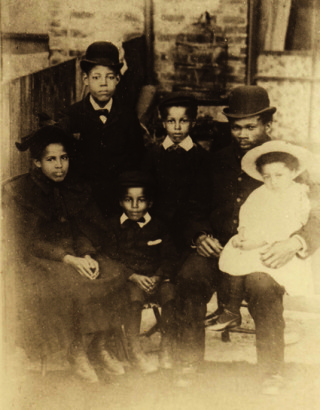

Daniel and Alice had six children, Bertha, who died in infancy, William, Cecillia, Edward, Walter and Elsie. They lived in 16 Allendale Street, Folkestone, where Walter was born and later moved nearby to 51 Walton Street, Folkestone. Walter and his siblings went to North Board Elementary school, now called Mundella Primary School.

Sadly, in 1895, Alice, aged 42, died leaving Daniel to bring up his children alone. A year after his wife’s death death, Daniel married her niece, Clara Palmer. They had a daughter, Miriam. On the 10 December, 1897, the family suffered another tragic loss when Daniel suddenly died of a heart attack, leaving Clara, aged just 27, to bring up six children.

Life in 1897 was very different to what it is today. Clara had to rely on charity to help feed her six children and pay the rent. Only William was working. Clara looked to her place of worship, the Grace Hill Methodist Chapel for support. It was decided that Edward and Walter would go to an orphanage while the other children would either work or help Clara at home with baby Miriam and the household chores. On a cold winter’s day, 24 February, 1898, the boys entered the Children’s Home and Orphanage, Bonner Road, Bethnal Green, East London.

Nothing could have prepared the boys for the shock of arriving in the largest city in the world. Sprawling with people, with noises and smells that overpowered, it was a far cry from the rolling hills and fresh sea air they were used to. East London, in particular, was notorious for its poverty and homelessness. Many children lived and begged on the streets. The boys arrived at the Children’s Home unsure of what their future held for them.

Orphanage

The Children’s Home and Orphanage was founded by Dr Thomas Stephenson, a well respected Methodist minister, who in 1869 was so moved by the plight of children living in East London, he opened his first children’s home; by 1908 the organization had grown into the National Children’s Home and Orphanage (NCHO).

For the next two years Walter and Edward lived together at the orphanage. They kept in close contact with their family back in Folkestone; they would often go back to Folkestone during holidays. Walter joined the orphanage football team and Edward, the orphanage choir. In the autumn of 1900, Edward went on a money raising tour with the choir. He was spotted by a Glaswegian family who were struck by his beautiful voice.

In November 1900, Edward was adopted by the family and moved to Glasgow leaving Walter alone at the orphanage. Fortunately for both Walter and Edward, the Glaswegian family was keen for the Tull family to remain in contact, and would frequently invite Walter and his family to their home in Scotland. The father of the family was a dentist and in later years, Edward took up dentistry as a career.

Walter was a keen sportsman and his passion for sports probably helped him get through the next 8 years without Edward, whom he’d always been very close to. He excelled at cricket, but it was football that captured his imagination. After completing his elementary schooling Walter was apprenticed to the Home’s printing department.

Professional Footballer

In October, 1908, Walter won a trial with Clapton F.C. and was in the first team in less than 3 months! During the 1908-1909 season, Walter helped Clapton win three competitions; the F.A. Amateur Cup, the London Senior Cup and the London County Amateur Cup. Walter was quickly spotted by larger clubs and in 1909 signed with Tottenham Hotspur, making him the first black outfield player in the English top division. He played for the North London side during their summer tour of Argentina and Uruguay. Playing at centre forward the Buenos Aires Herald noted ‘early in the tour Tull has installed himself as favourite with the crowd’.

A year after playing on Victoria Park, Bethnal Green for the Orphanage football team Walter was making his Football League debut in Spurs first ever game as members of the top division, against Sunderland at Roker Park, 1 September, 1909. Two weeks later Walter’s made his home League debut against FA Cup winners Manchester United. Brought down for a penalty, the conversion resulted in a 2-2 draw, Spurs first point of the season.

In an overly physical game at Bristol City on 2 October, 1909, Walter was the target of racist abuse from the home supporters. Casual racism was the norm at the time, with match reports referring to Walter as ‘darkie Tull’. The Football Star described the Bristol City fans racist language as ‘lower than Billingsgate’, code for saying it was cruel and vicious. Another paper reported ‘a cowardly attack on him’ by a section of the Bristol City support. This treatment of Spurs’ ‘most brainy forward’ angered a reporter for the Football Star who wrote; ‘Let me tell those Bristol hooligans that Tull is so clean in mind and method as to be a model for all white men who play football…the best forward on the field.’

The incident at Bristol embarrassed some Spurs officials. Soon after, Walter was dropped to the Reserves, making only three more appearances in the first team. However, his long, tough years at the orphanage taught him how to handle situations when others tried to put him down. In 1911 Walter was sold for ‘a heavy transfer fee’ to Northampton Town, nicknamed the Cobblers. Their manager, Herbert Chapman, was later to become one of the greatest managers ever at Arsenal F.C. Chapman was a Methodist like Walter and had once played for Arthur Wharton, England’s first black professional football player, at Stalybridge Rovers. He was not interested in Walter’s colour, only his skills as a player. Walter played over 10o first team matches for the Cobblers and was a crowd favourite. Walter and Chapman certainly proved wrong those at Spurs who did not stand by Walter in his time of need. In July 1999 Northampton erected a memorial in Walter’s honour, later naming the road to their Sixfields Stadium ‘Walter Tull Way’.

In August, 1914, war had been declared and 1000’s of men enlisted to join the army. On the 21 December, 1914, Walter volunteered for the Football Battalion (17th Middlesex Regiment), he was the first Northampton player to join the army; he viewed enlisting as his responsibility and duty to his country in a time of great crisis. He joined other great footballers of the time in the military, including Vivian Woodward who played for Tottenham Hotspur, Chelsea and England. Walter and Vivian would become good friends. Walter continued to play for Northampton until the end of the season.

In 1917, Walter signed up to Glasgow Rangers, playing for Rangers would mean that once the war was over he could once again live close to his brother, Edward; sadly this would never happen.

Army Officer

During his military training Walter was promoted three times. In November 1914, as Lance Sergeant he was sent to Les Ciseaux in France. He was positioned very close to the front lines, so close that he would have easily heard the great guns booming in the distance as he lay in bed at night. In May, 1915 Walter was sent home with acute mania, now called post traumatic stress disorder.

Returning to France in September 1916 Walter fought in the last months of the Battle of the Somme, between October and November, 1916. This battle saw some 420,000 British troops killed in just 4 months. His courage and soldiering abilities encouraged his superior officers to recommend him as an officer. On 26 December, 1916, Walter went back to England on Leave and to train as an officer.

After spending six weeks with family and friends, on 6 February, 1917, Walter presented himself at Number 10 Officer Cadet Battalion, Gailes, Scotland. This was despite military regulations forbidding those who were not of ‘Non- European descent’ from becoming officers. Walter received his commission as an officer 30 May, 1917, in spite of the fact that it was technically illegal. The military’s colour bar didn’t change until the Second World War.

2nd Lieutenant Walter Tull was sent to the Italian Front and became the first black officer in the British Army to command white troops. He twice led his Company across the River Piave on a raid and both times brought all of his troops back safely with out a single casualty. He was mentioned in Despatches for his ‘gallantry and coolness’ under fire by Major General Sir Sydney Lawford, his commanding officer. He was recommended for the Military Cross but never received it.

After their time in Italy, Walter’s Battalion was transferred to the terrible Somme Valley in France. On March 21, 1918, the Germans made one last desperate effort to win World War One. Walter Tull was a 29 year old 2nd Lieutenant in the 23rd (2nd Football Battalion) Middlesex Regiment, when he found himself in the British trenches facing advancing Germans.

On 25 March, 1918, 2nd Lieutenant Tull was killed by machine gun fire near Favreuil aerodrome trying to help his men retreat. Several of his men including, Leicester goalkeeper, Private Tom Billingham, attempted to retrieve his body under heavy fire but were unsuccessful due to the enemy soldiers advance. Their brave actions are a testament to Walter Tull’s character and leadership qualities. Walter’s body was never found and he is one of thousands of soldiers from World War One who have no known grave.

No Known Grave

Having no known grave, his name is inscribed on Bay 7, Arras Memorial, Faubourg-d’Amiens Cemetery, Arras, France. In 1999 Walter Tull’s former club, Northampton Town, erected a memorial outside of Sixfields Stadium, naming the road to the stadium “Walter Tull Way”. In 1921 Walter’s family in Dover ensured that his name was inscribed on the Parish Memorial at River, and in 1924 on the Dover Town Memorial.

Further Resources

Walter Tull was the focus of an earlier City of Westminster Archives project called ‘Crossing the White Line’. The educational resources and animation are available to download and view here.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page