The Football Battalion

Recruitment and sport

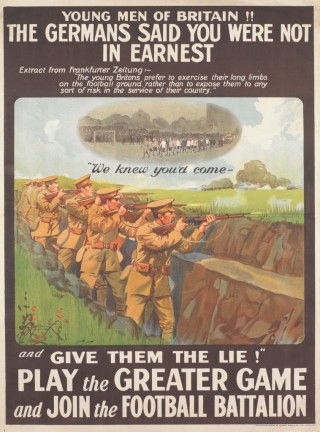

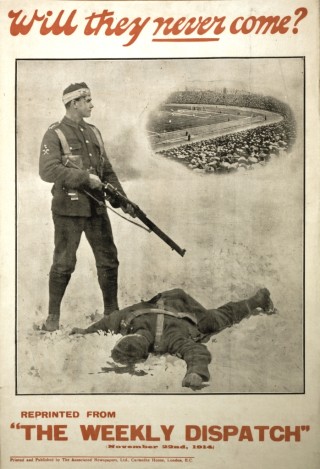

The declaration of war in August 1914 coincided with the start of the 1914-1915 football season. As Lord Kitchener pushed for 100,000 new recruits to join the army, the Football League came under pressure to abandon the league programme so that both fans and players could ‘play the greater game.’

Wellington’s belief of a century earlier that success on the battlefield could be traced back to the playing fields of Eton was still a widely accepted view amongst Britain’s elite. Both Mr Punch and The Times depicted war in such a way. From a modern perspective it is hard to understand what appears to be the trivialisation of war. The Times, on the 24 November 1914, published a poem The Game which made clear its expectations:

‘Come, leave the lure of the football field with its fame so lightly won,

And take your place in a greater game where worthier deeds are done.’

Chelsea Football Club

Chelsea’s gentleman amateur captain, Vivian Woodward, had joined the 17th Football Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, whose formation had been the idea of Fulham M.P. and Arsenal director, William Joynson Hicks, as a way of recruiting football fans. Woodward marched around the pitch with members of the battalion appealing to fans to join up. The poor response from Chelsea fans appeared to be in direct contrast to successful recruitment drives amongst rugby players and sportsman from public schools. A thinly disguised class bias seemed to depict followers of the working man’s game as ‘shirkers,’ despite The Chelsea Chronicle’s claims to the contrary. That 2000 out of 5000 professionals had already joined up and over 300,000 amateur players enlisted seemed to escape the notice of the critics.

One young lad who did heed the call was James Ridley. As a 13 year old living opposite Stamford Bridge he had volunteered as a ball-boy, a first in the Football League. He had even sneaked into the first Chelsea team photograph so he could be seen with his idols. Ten years later, in 1915 he was serving alongside them in the trenches as a soldier in the Football Battalion. He became a Prisoner of War when he was captured at Cambrai in 1917 but survived the war.

Professional football finally came to an end following Chelsea’s first appearance in the F.A. Cup Final on 24 April 1915. The ‘Khaki Cup Final’ was played at Old Trafford and Chelsea lost 3-0 to Sheffield United. Vivian Woodward had received special permission from his battalion commander to play and raced up to Manchester only to give his place in the team to his replacement Bob Thompson, as he did not wish to deprive his fellow team mate of a cup final medal. With the ending of professional football, players effectively had no choice but to join up. One such player was Jack Cock, who had grown up in Fulham before becoming a pre-war star with Huddersfield Town. He joined Woodward in the Football Battalion and at the end of the war joined Chelsea, scoring England’s first post war international goal.

First Black Officer

Perhaps the most remarkable story associated with the Football Battalion was that of former Spurs and Northampton professional Walter Tull. Britain’s first black professional outfield player, Tull also became Britain’s first black combat officer before his tragic death at the second Battle of the Somme in October 1918. Tull confounded the social and class barriers of his era to succeed against all the odds.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page